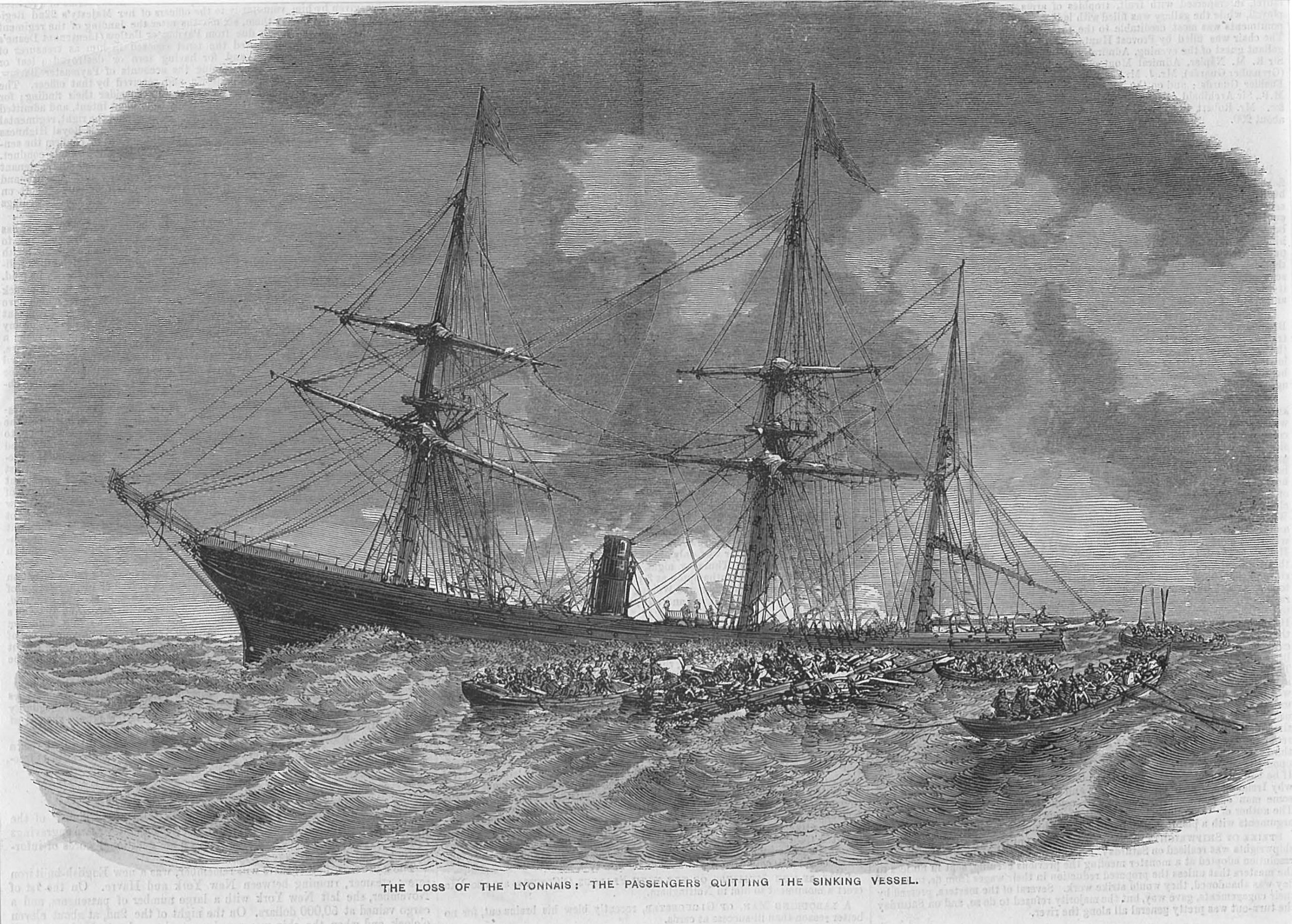

Colorized Illustrated Times of London drawing of LYONNAIS’ sinking, December 27, 1856. (From Jennifer Sellitti)

There are thousands of vessels that have met their fate off the shores of New England over the last six hundred or more years. Many of these occurred on the shores or within sight of land and their accounts are well known. Others were well offshore with only an approximate location, while others simply went missing somewhere out in the Atlantic. In August it was announced that a group of shipwreck divers from Massachusetts, Atlantic Wreck Salvage, had located the 260-foot French steamer LYONNAIS, which had been lost off that coast following a collision with the Belfast built bark ADRIATIC on 2 November 1856. LYONNAIS took down with her 114 crew members and passengers and the disaster would evolve into an international incident over the next two years.

Eric Takakjian, a shipwreck diver from Fairhaven, Massachusetts, started searching for wrecks, which had occurred well off the Massachusetts coast. One he had learned about was the steamer LYONNAIS, which he began searching for in the late 2000s. For years he searched in vain and would later combine his efforts with Atlantic Wreck Salvage (Joe Mazraani and Jennifer Sellitti) in 2016. The group did side-scan sonar runs over a wide area and discovered several targets. After reviewing the information they narrowed their search to a few possible targets. On 20-25 August 2024, the team returned and discovered one of the targets as LYONNAIS, which was located 140 miles off of Nantucket, Massachusetts on Georges Bank. Unfortunately, the harsh marine environment has caused a lot of damage to the vessel. The direct acting horizontal steam engine was located and with other artifacts from the wreck they confirmed her to be LYONNAIS.

The 1,070-ton LYONNAIS was built by Laird & Sons of Birkenhead, England for Compagnie Franco-Americaine in 1855. Her construction took place during the transition from sail to steam, paddle to screw, wood to iron, thus she has steam for her primary propulsion with sails as a back-up. She was built with five water-tight compartments and considered a staunch vessel and would stay afloat even if only two compartments were free of water. Her value was $350,000, and was fully insured, mostly in France. She was built to run passengers across the Atlantic from Europe to America and made her maiden voyage in January 1856. When LYONNAIS departed New York City for Le Havre, France just before the collision she had onboard 132 crew members and passengers under the command of Capt. Devaulx.

The 397-ton 123-foot bark ADRIATIC was built by Patterson & Carter Co. of Belfast, Maine for Patterson & Carter, Barnard, Jonathan and Charles Durham, J. Havener and others and launched on 11 October 1856. This was the first vessel this company had turned out. She was named for a body of water in the Mediterranean Sea, which was quoted in Lord Byron’s “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” Canto iv. Stanzas 11–13:

THE SPOUSELESS Adriatic mourns her lord;

And, annual marriage, now no more renew’d,

The Bucentaur lies rotting unrestored,

Neglected garment of her widowhood!

St. Mark yet sees his lion where he stood,

Stand, but in mockery of his wither’d power,

Over the proud Place where an Emperor sued,

And monarchs gazed and envied in the hour

When Venice was a queen with an unequall’d dower.

On 31 October 1856 ADRIATIC sets sails from Belfast for Savannah, Georgia on her maiden voyage under the command of Barnard Dunham. She had on board a load of lime and hay.

The Republican Journal of 14 November had a brief statement that ADRIATIC was run into by an unknown steamer on the night of 2 November. They added that ADRIATIC had put up lights so as to be seen, but the steamer held course striking the bark forward carrying away her bowsprit and forward bulwarks. The steamer failed to stop and render assistance. ADRIATIC put into Gloucester for repairs on 4 November.

The next week’s issue of the “Journal” had more information. It was now known that the steamer was LYONNAIS and was carrying 38 passengers, 94 officers and crew with a cargo valued at $46,000 and $20,000 specie. LYONNAIS was described as being a total wreck and all those on board were reported as having left the vessel in lifeboats or rafts. On 9 November the German bark ELISE discovered one of the lifeboats and took these survivors on board, later to be transferred to the German bark ELISE, who took the survivors to New York City. At this point there were still hopes that other survivors had been picked up, but as yet no word had been received.

It was reported that the night of the collision was dark and it was blowing a gale. Capt. Dunham said that they noticed the steamer when she was a mile distant. They set lights and tried to hail the steamer. The steamer changed her course and to avoid a collision the bark was brought to the wind and struck the steamer at the paddle box. [Interesting, as she was a screw steamer and had no paddle boxes.] It was now thought that the first accounts of the collision were inaccurate.

The next week, Capt. Dunham stated, “On Sunday night, November 2d, before 11 o’clock, the bark steering by the wind, heading WNW, discovered a steamer about three or four points on the weather bow, supposed to be steering ENE. The night was starlight, but hazy; should think we saw the light 20 minutes or more before we struck. The steamer continued her course, which would have carried her by our stern, if not altered, but upon nearing us she suddenly changed her course, which rendered a collision inevitable. We then endeavored to save ourselves by tacking, but it was too late and in a few minutes we were afoul, striking the steamer abaft the wheel house carrying away our jibboom, bowsprit, and starting the whole starboard bow from the deck frame, and the wood ends forward. We then hailed the steamer and requested them not to leave us, but received no answer. We then kept away before the wind to prevent losing our masts, and to ascertain the extent of our damage. Saw the steamer’s lights about four points on our lee bow, and kept in view ten or fifteen minutes, until lost in the distance. Supposed that she had received but little damage, and had continued on her course. We secured our masts and repaired the damage as well as possible, and then shaped our course for the nearest port, and arrived at Gloucester, November 4th, at 11 P. M., and reported myself to the Custom House and to the Reading Room, stating the full particulars. The statement with regard to the weather being foggy is entirely incorrect, as it was starlight, with a slight haze in the atmosphere.”

A statement by the mate of LYONNAIS said, “cleared at the Custom House of New York, and sailed for Havre on the 30th of October at 2 P.M. After quitting the pilot at 5 P.M., we made good way, and at noon the following day, (Sunday) were 195 miles averaging ten knots an hour. About 11 P. M., the night dark, the ship running eleven knots, under sail and steam, and displaying lights according to regulation, the man on the lookout called “A ship to starboard, bearing down on us under full sail!” The whistle which had been put on board at New York, and which can be heard ten miles off, was immediately sounded. The helm was put hard-a-port on the instant; but nevertheless, a three-masted vessel struck the LYONNAIS across the companion way amidships. The bowsprit of the ship broke with the concussion, and stove in the side of our vessel from the companionway as far as the shrouds, seriously damaging the two starboard boats, one of them an English lifeboat. The collision broke away the iron plates of the coal bunkers, letting in the water. We continued on our course during about ten minutes; but the water almost immediately extinguished the fires. The unknown vessel, in clearing away from us, left on the deck of the LYONNAIS part of her figurehead, representing a black dragon, with gilt mane, red eyes, open mouth, with gilt dart in it. At the moment of collision, Capt. Devaulx rushed to the wheel; the first lieutenant, Mr. Gustave Matthieu was on the watch, and Deponent was at his post on deck. As soon as the engines stopped, Mr. Gigneux, the chief engineer, came up from below and declared that the water was pouring in at the coal bunkers and the ship was sinking. The pumps were immediately set going, but floating cinders choaked up the valves, and they became useless. We then had recourse to buckets and formed a chain, whilst part of the crew and some of the passengers went below to shift the cargo from starboard to port, but as the water continued to rise, the captain ordered the cargo to be thrown overboard. During this time some of the passengers – amongst them two old sea captains – a few officers, a number of sailors were busy covering the side of the ship with a large stuffing sail, whilst the carpenters from the inside were endeavoring to stop the leak with mattresses, quilts &c. The opening in the side of the ship was at the waterline, and appeared to be two feet square. Our exertions were of no avail, as the sea was growing rough, and we were unable to careen the steamer. Although over a dozen mattresses and similar articles were propped against the hole, it became impossible to withstand the pressure of water. We commenced sheathing the ship outside with large awning, which seemed to stop the leak for a time. During all this the bailing never ceased, but as we found the water increased rapidly, the conviction was forced upon us that a second hole existed beneath the water line. Notwithstanding throwing overboard the cargo, and then continued bailing out, the ship was sinking rapidly by the stern. Two large casks were then used to bail the water, the captain and officers landing a helping hand with the tackle. For a moment we thought the water was decreasing, but it soon overpowered us. The bailing had lasted from 8 A. M., to 3 P. M., and the men were exhausted with fatigue.

“The captain then lowered the boats and embarked the passengers and crew. In order to be prepared for the worst, a raft had been built during the day, of top masts, spars, cabin doors, boards, chicken coops, etc., etc., and on it were placed two barrels of wine, two puncheons of water, and various kinds of eatable, sufficient to last the fifty persons placed upon it at least a month. In the first cutter were some twenty-five persons, amongst whom were the first and second engineers, the steward, his nephew, all the cabin servants (ten in number); this boat was under the command of the chief officer, Mr. Russell. This boat had on board compass, charts, chronometers, a sextant, and provisions for two weeks, with complete set of new sails. A second boat, same size of the former, took off twenty-five persons; she had the same amount of food, nautical instruments and new sails as the first cutter, and was under the command of the two sea captains. A lifeboat, containing about twenty persons, and having, like the other, a complete set of sails, provisions and instruments, was placed under the orders of Mr. Dublot, third Lieutenant. Another lifeboat, containing eighteen persons, with provision for two weeks, was placed under the command of Deponent. The various boats, once equipped, were kept during the night in the neighborhood of the wreck, the captain remaining on board the latter with the first Lieutenant, four petty officers, stewardess, and Messrs. Claisin and Bonestae, the doctor and purser. Two yawls, which might each hold six person, were moored to the wreck. During the night the lifeboat commanded by Mr. Dublot, which had been damaged at the moment of the collision, was carried by the waves against the raft, and immediately sunk; those in her were rescued by the raft.

“At 7 o’clock A. M., on Tuesday, the 4th inst., the captain, perceiving that the ship could no longer float, and was likely to sink every moment, ordered those on board to embark in the yawls; he, himself, was the last to quit the ship. Before the officers took to the boats under their respective commands, the captain called them into the deck house of the steamer, and pointed out to them on the chart the spot in which they were, and explained to them the direction they must follow, in order to reach the nearest land. At 8 o’clock A. M., the three boats made headway towards northwest in company. On quitting the wreck, the captain was seen with his men in one yawl, and first officer with purser in the other, near the raft. The captain declared his intention of remaining by the wreck until the LYONNAIS sunk. The raft was moored to the hull with a ten fathom hawser, and a man stood ready with an axe to cut loose when she sunk.

“The boats kept company until 5 P. M., when a thick fog set in, and Deponent being to leeward of the other two, lost sight of them. He put about to rejoin them, but not finding them, he continued his course towards the northwest, without compass or instruments. At 9 P. M., wind commenced blowing from north, and during three following days he ran before the wind, it blowing a gale. Passing over the banks, two men were frozen to death; one a fireman, the other a passenger about sixty years of age – name unknown. Threw, the bodies overboard. The survivors, Deponent included, suffered horribly from cold, snow and hail falling incessantly, whilst the sea breaking over them had spoiled nearly all their bread and provisions.

“6th. – At 6 P. M., saw a schooner to windward, but the state of the sea would not allow us to reach her.

“7th. – Heavy swell, tempestuous sea, but rather moderating. Had little rest during the day. Evening, a calm.

“8th. – Early in the morning saw a three masted vessel about five miles off. Pulled towards her, but taking no notice of the signals made by us, she kept on her course towards the north. We followed in the same direction.

“9th. – Sunday. – About 8 A. M., saw a sail near horizon. Rowed towards her, but a breeze springing up, and the ship going in the same direction as ourselves, we could not reach her. It was at this time that Deponent saw another sail on the port side, bearing down towards them. After three hours of fatigue and hard rowing, we reached her, and found her to be the bark ELISE, of Bremen, Capt. Nordenbolott, bound from Baltimore to Bremen. The captain took us all on board, and seemed happy in giving all the care and attention required under the circumstances. Our boat, with all it contained, was hoisted on board. Deponent asserts that with the courage and energy displayed by his men, they could have kept the sea in their boat, four days longer, which fact leads him strongly to believe that the other boats will also be picked up.

“10th. – At 7 A. M., the vessel on which they were spoke another of the same name, from Hamburg, going to New York with 150 German emigrants. The captain, in the most kindly manner, for which he cannot be too highly praised, and regardless of his great number of passengers, consented to take those of us on board who desired to return to New York. All availed themselves of this offer, with the exception of Mr. Schedell (late British Vice Consul) and his wife, who preferred Bremen. After four days sail, the bark ELISE landed us at New York, the 14th November, at 5 P. M.”

On 5 December another account appeared in the “Republican Journal” discrediting the account claimed by the second officer of the LYONNAIS. The first question was raised at the course they were running. If the wind was SW and the bark sailing WNW, jammed on the wind and the steamer running ENE and on the bark’s port bow what course was each on? The one questioning the course said their positions were reversed with the steamer being down on the bark. He added that the steamer would have passed astern of the bark, but changed course within two cable lengths. It was also thought if the steamer did not know which course the bark was sailing, she should have stopped. In close quarters a sailing vessel is required to hold her course and not alter it for a steamer. Capt. Durham only changed course after the steamer did and this caused him to put into the wind and hit the steamer bow on, otherwise the steamer would have hit the bark amidships, mostly likely a fatal blow. As to the bark standing by and lending assistance if needed, the person said that none was asked for. Adding that ADRIATIC had to stand before the wind in order to prevent her masts from going by the board. Capt. Dunham did say that if he had heard a distress call he certainly would have lent assistance. There was also a question as to why the boats that were the last to leave the steamer were not provisioned well and that some of the people did not have proper clothing on. As to the regulations regarding an ocean steamer’s boat they are to have oars and 15 gallons of water.

The editor of “Life Illustrated” placed the blame for the collision on Capt. Dunham, but was quickly taken to task for his lack of knowledge of the rules governing steamers and sailing vessels. Since both vessels had seen each other it was the responsibility of the steamer to stay clear of the bark. Others in the media soon took to attacking Capt. Durham.

On 10 February ADRIATIC arrived at Le Ciotat, France after sailing from Savannah, Georgia with a cargo of wood. Ten days later she was ready to sail, but was seized and the captain arrested by French authorities. Messrs. Gauthier Brothers, owners of LYONNAIS had filed papers with the court seeking compensation for the loss of their steamer. Capt. Dunham sought the protection of the American Consul at Marseilles. It was expected that the captain would be tried in a French court. It was remembered that the collision between the French vessel VESTA and American Collins liner ARCTIC, which caused a large loss of life on the American steamer, there was no retaliation. The French still claimed that they had jurisdiction in this case.

On 1 May 1857 the “Journal” published a French article on the judgement in favor of Capt. Dunham. All the evidence was presented from both sides. The authorities came to the conclusion that Capt. Durham was not at fault. The owners did not prove that ADRIATIC was required to show a light in American waters and it was noted that once the steamer was sighted the bark did show a lantern. It was also stated that after the collision LYONNAIS continued on her course and that was a major factor in eliminating the accusation that the captain of ADRIATIC did not stand by to lend assistance. Thus, ADRIATIC was free to leave port. Capt. Durham then sought damages, but this was not allowed by the court.

On 29 January the saga continued as the “Journal” reported that an appeal had been made and that the Court of Appeal at Aix had reversed the judgement against Capt. Durham declaring the collision his fault. They said that because the captain had sailed without lights, even though not required, it was not prudent and thus the collision was his fault. What is interesting is that the underwriter’s had already paid the owners of LYONNAIS for the loss.

In the same issue of the “Journal” it was stated that ADRIATIC would be condemned and sold at auction. Well, in the next issue it was announced that ADRIATIC had slipped out of the port of Marseilles without the proper papers and was out in the Atlantic.

ADRIATIC had been unrigged during the second trial. However, the ship MEAHER, Capt. Smith, was also in port due to debts she owed. The two captains devised a plan where the MEAHER would come along side the ADRIATIC, MEAHER’s cargo was then transferred and her rigging placed on ADRIATIC and at 0300 on 9 January she slipped her anchor and headed out of port. But before she could clear, a boat from the Custom House asked if her papers were in order to which the captain replied that they were. He then asked what vessel is she and the response was the LUNA, which had cleared the day before.

ADRIATIC was not discovered missing until first light. The French sent out the paddle steamer CHUCAL in search of the bark and she had not returned. This gave rise to the thought that she might be hid in a creek on the Spanish coast. It was also stated that Capt. Smith had also transferred three guns, some other arms and powder to ADRIATIC.

The French then applied to Washington for reparation for this outrage. Some saw this as a personal battle between Capt. Durham and the French authorities, and should not include the American government.

It is interesting how some of the testimony regarding the events that took place the night of the collision were altered over time. In the “Journal” there was a statement made by a passenger named Mr. Schedell, who was on board the steamer told in mid-February. He told the American Consul in France that the officer of the deck was a young man, a nephew of the captain, that the crew would not obey. When he saw the bark he had given the wrong order. The captain ran up on deck and he could not correct the order before they collided.

ADRIATIC was reported to be at Spezzia and a French warship was sent out to capture her. Capt. Durham was asked for a bill of health there and when he could not produce one, he was not permitted to land. The captain went ashore and met with the American Consul, who told him that the French had alerted the Sardinians and they were told by Turin to capture her. The Sardinians placed a gunboat under her stern with the threat she would be blown up if she tried to escape. However, those orders were withdrawn and she was not to challenged. A storekeeper from the United States replenished the vessel, but as this was taking place the wind began to build. She was riding on a kedge with 45 fathoms of chain and a chain box filled with stone as a back-up. ADRIATIC continued to drift and they are compelled to run a hawser ashore. Capt. Durham went to town, received his ship’s papers and set sail. The next day she fell in the ship ELIZABETH DENNISON, who gave her more provisions and an anchor. She slipped out of the Mediterranean and disappeared across the Atlantic.

On 29 January ADRIATIC was spoken to off Cape Palos heading for New York.

In March the affair of the ADRIATC was heard before the house of Congress. Mr. Miles Taylor of Louisianna offered a resolution for redress for the owners of ADRIATIC and the prevention of this happening in the future. It was deemed that a foreign country does not have the right to seize an American vessel when that vessel was conforming to the rules of the United States and the incident happened in United States waters. This was all referred to the committee on Foreign Affairs.

On 18 March ADRIATIC arrived at Savannah, Georgia. It was not an easy voyage having calms and head winds much of the time. With an exhausted crew and not much left for provisions they made the nearest port, which was Savannah.

Capt. Durham was later noted to have been in Washington, a guest of Dr. A. C. Jordan, formerly of Bangor. While there he met with the President and gave him all the details of the incident. There was hope that a diplomatic solution would be found. In June Mr. Burlingame’s report was accompanied by a resolution asking the President to obtain redress from the French. The report also asked for a revision to the laws governing collisions at sea and an arrangement for compensation for damages.

It was also learned that one of the Gauthier Brothers had made false entries in their ledgers increasing their return on profits and was now in prison.

The following year the bark ADRIATIC was offered for sale, freight or charter in the “Savannah Republican.” The advertisement read, “The ADRIATIC is a superior vessel, of 400 tons, and has been fully tested, both as to strength and speed. She “will do travel,” and if any are in doubt on the above points, we refer them to the French!

In the fall of 1860, the bark ADRIATIC was at the harbor of Buenos Ayres when a Pampero struck. She was weathering the storm until a drifting Buenos Ayres man-of-war threatened to hit her. The captain ordered more chain let out, but the chain parted and she drifted down toward a Norwegian brig and released a third anchor. Before the anchor took hold, she struck the brig suffering heavy damage. She then struck the anchor and this created a sizeable leak. She was surveyed and condemned the end of July. She was to be sold in August and was only partially insured. This ended the very interesting career of the bark ADRIATIC.

Atlantic Wreck Salvage team member Jennifer Sellitti has also written a new book entitled “The Adriatic Affair: A Maritime Hit-and-Run Off the Coast of Nantucket.” (Schiffer Publishing, $34.99, Hardcover, on sale February 28, 2025) which will provide an in-depth history of the ADRIATIC and LE LYONNAIS hit-and-run, as well as more information on the sinking and survivors. The epilogue covers the details of the search and discovery of LE LYONNAIS, as well as additional underwater and topside photographs from the expedition. The Adriatic Affair is available now for pre-order wherever books are sold or https://www.amazon.com/Adriatic-Affair-Hit-Run-Nantucket/dp/0764367951/